The Birobidjan Folio

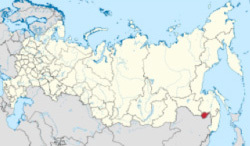

Birobidzhan (also Birobidjan) was first settled in 1928 as an autonomous, Jewish homeland in Siberia, about 5,000 miles east of Moscow in a sparsely populated region annexed by Russia in 1858. It was one of many ethnically defined territories Lenin designated in an effort to create a unified socialist culture. Communist officials hoped that Jews would farm the remote soil, become secularized, and as a result, integrate more fully into Russian society. Between 1928 and 1938, more than 35,000 migrants moved from within the USSR to Birobidzhan, which was incorporated as a town in 1937.

The region was mostly marshy territory, twice the size of New Jersey. Its geographical climate was extremely challenging: brutally cold in winter, unbearably hot in summer, and plagued with mosquitoes, mud, disease, and flooding. The Soviet government did not provide the settlers with adequate housing, food, medical care, or working conditions; as a result, they were poorly equipped and untrained to successfully farm. Furthermore, despite the expectation of fostering an agricultural economy, few Jews pursued farming, taking jobs in retail and the service sector instead.

ICOR, a Yiddish acronym for the Association for Jewish Colonization in the Soviet Union, encouraged Jews worldwide to move to Birobidzhan and helped raise funds to support the collective farms. Supporters of ICOR believed it would be easier to move European Jews to Birobidzhan than Palestine—and a way to protect them from persecution, which was escalating after the Nuremberg laws were passed in Germany.

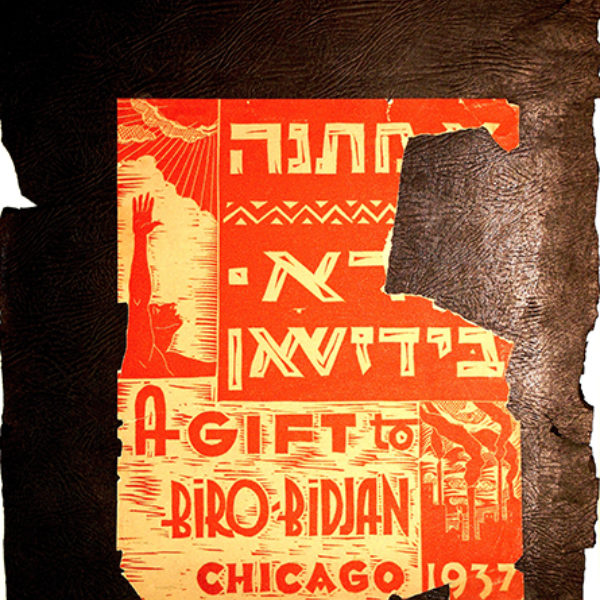

In 1937—at Birobidzhan’s height—the Chicago chapter of ICOR commissioned a portfolio of lithographs to support the settlement. For artists in Chicago, the Birobidjan project represented Jews’ continuous striving to find a peaceful homeland. The portfolio comprised fourteen woodblock prints in an edition of two hundred—though it has been speculated that fewer were actually produced. Not many complete copies are known to exist beyond the one in this collection (three are found in Chicago institutions: the Spertus Museum, Mary and Leigh Block Museum at Northwestern University, and Koehnline Museum at Oakton Community College; and one in the Whitney Museum, New York).

The fourteen artists were free to choose their own subjects within the portfolio’s theme. The cover image illustrates the subtitle’s message “From despair to new hope” with smoke rising from industrial chimney stacks at the bottom while a muscular arm and hand reaches toward the sun in the top left. The cover design was likely created by Todros Geller, who also contributed a print, Raisins and Almonds, named after a Yiddish poem of the same title. It shows a montage of a young man’s life, from infancy in the lower right, to school, trade as a tailor, past a market, and on to the big city in the new world, with high rises and elevated trains. There, he is able to plant a tree in a gesture of “new hope.”

Many of the prints depict workers: for instance, Fritzi Brod’s image of seamstresses, In the Workshop, or Morris Topchevsky’s To a New Life, which shows a pioneer couple walking away from a bearded, traditional Jewish figure and holding blueprints and an axe. Mitchell Siporin’s Workers Family captures a typical Depression-era scene of a family in front of an industrial landscape. The carefully rendered facial features of three generations of family members (a boy, his parents, and his grandfather) stand out against the dark factory buildings in the background. The narrative conforms to the socialist ambitions of Birobidzhan—a family working together to forge a new future. In Edward Millman’s Shoemaker, the artist emphasized the tradesman’s large hands, a sign of his background as a skilled worker in the old country, while the shoes he works on symbolize the wandering Jew looking for a home.

Abraham Weiner’s Milk and Honey echoes Grant Wood’s American Gothic (1930; Art Institute of Chicago), and adds a Biblical dimension to the iconic image of a working couple. In this woodcut, a man holds a goat and woman wields a rake—in a progressive image of labor and gender equality. Weiner implies that the woman will rake the promised land of milk and honey, blending a utopian vision with Biblical associations. Weiner’s skillfully replicated the lines of the rake over the entire composition. Another overt reference to the Bible is Raymond Katz’s image of Moses and the Burning Bush, which symbolizes the Jewish people’s quest for the promised land. A flame symbolizing both survival and continuity appears throughout the image.

Several contributions depict or allude to war in Europe. In Alex Topp’s Exodus from Germany, refugees flee a flaming swastika, an eerie premonition of Jews’ future in Europe. Bernece Berkman’s print, Toward a Newer Life, combines imagery of Biblical slavery and Jewish persecution in Europe and workers of the Great Depression in her signature combination of cubism and expressionism. William Jacobs’s Persecution, illustrates soldiers forcing refugees to march; only one individual resists, raising his fist in rebellion.

Others show the plight of the working classes during Great Depression in the United States. In Louis Weiner’s No Business, garment peddlers sell their wares on a street, heads down-turned, unable to compete with stores in the background where transactions are completed. Aaron Bohrod’s West Side depicts a man wandering the streets of Chicago with his possessions bundled over his shoulder. The image illustrates why Birobidzhan gained sympathy and support of left-wing Americans: the plight of Americans during the Depression shared a kind of solidarity with wandering, persecuted Jews of Europe. This contrast between the old and new Jew is also captured in David Bekker’s Bronx Express, in which a Yiddish man is surrounded and yet isolated amidst younger passengers on the train, as well as in Ceil Rosenburg’s New Hope. Here, the artist depicts a bearded, traditional, religious man whose haunting face represents history, looming over the shoulder of a young Jewish laborer, a secular pioneer with pitchfork—in another plausible riff on Grant’s American Gothic. It is both promising and ominous as the young man forges a future but can never detach from his past.

Lisa Meyerowitz

References

Baskin, Rebecca. “Back to Birobidjan.” Jerusalem Post (Oct. 14, 2009), http://fr.jpost.com/servlet/Satellite?cid=1255450652192&pagename=JPost%2FJPArticle%2FShowFull.

Bayne, Martha. “Lost and Found: A Mysterious Gift of Art. . .” The Reader’s Guide to Arts and Entertainment 6, no. 45 (August 16, 2002), 1, 6–7.

Harpaz, Nathan. A Gift to Biro-Bidjan: Chicago, 1937: From Despair to New Hope. Exh. cat. Des Plaines, IL: Oakton Community College, 2002.

Oakton Community College, A Gift to Biro-Bidjan: Chicago, 1937: From Despair to New Hope, http://www.oakton.edu/museum/biropro.html.

Weinberg, Robert. Stalin's Forgotten Zion: Birobidzhan and the Making of a Soviet Jewish Homeland. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Weinberg, Robert. Stalin’s Forgotten Zion: Birobidzhan and the Making of a Soviet Jewish Homeland, an Illustrated History, 1928–1996. (website) Swarthmore College, 2001. http://www.swarthmore.edu/Home/News/biro/.

Map Image: Birobidzhan, Russia; credit: Wikimedia Commons.