Samuel Himmelfarb

b. 1904, Latvia - d. 1976, Chicago, IL

Samuel Himmelfarb was born in Latvia in 1904, but moved to the United States at a young age and spent his early years in Wisconsin. He began his formal art education at the Wisconsin School of Fine Arts, Milwaukee State Teachers College, under German-born artist Gustave Moeller, and at the University of Wisconsin, Madison (1924). Himmelfarb pursued further instruction in New York City, where he studied at the National Academy of Design (1926) and with Boardman Robinson at the Art Students League (1929).

Himmelfarb worked for several architecture firms in New York, but returned to the Midwest in the early 1930s and settled in Chicago with his wife, Eleanor, also a painter. After designing several exhibits for the 1933 Century of Progress Exposition, he founded the industrial exhibition firm Three Dimensions. The company provided a steady income for Himmelfarb while he pursued a career as a fine artist. From the 1920s through the 1950s, Himmelfarb exhibited his work widely, including group shows at the Wisconsin Painters and Sculptors Exhibitions in the early 1920s and 1938, the Arts Club of Chicago (1952–55), in the National Circulating Exhibit by the American Federation of Arts (1953), and in numerous exhibitions at the Art Institute of Chicago (1935 to 1957), where his Men on a Boat won the James Brodas Clarke Memorial Prize in 1949. Solo shows at the Milwaukee Art Institute (1932), the Panoras Gallery in New York (1956), and the Frank Ryan Gallery, Chicago (1958), also generated critical and popular interest in his art.

Produced nearly two decades apart, the Friedman collection paintings represent distinct moments in Himmelfarb’s stylistic evolution over the course of his career. Yet both pictures manifest the artist’s desire to “explore and discover the vitality and drama of the insignificant . . . the latent excitement in the unspectacular,” as Himmelfarb declared in a 1958 interview for Inland Architect. Road House (1927) dates from Himmelfarb’s years in New York and recalls earlier twentieth-century works by the Ashcan school artists, such as John Sloan’s McSorley’s Bar (1912, Detroit Institute of Arts). Himmelfarb’s painting exemplifies his interest in “the casual human scene,” in both its humble setting—the sparse interior of a roadside bar—and its commonplace subjects. In the foreground, two women—one seated upon a bar stool, the other, turned away from the viewer at the left—primp and preen unselfconsciously. The barman is similarly caught unawares as he slumps disinterestedly over the counter. Only the man seated by the bulging potbelly stove at the center seems aware of the viewer. The aloofness of the figures and the lack of conviviality in the painting, combined with its plunging perspective, strong lighting effects, and loose brushstrokes, may also owe a debt to modernist French art. Café and bar scenes by artists such as Edgar Degas and Édouard Manet, for example, strongly influenced turn-of-the-century American depictions of dining and drinking.

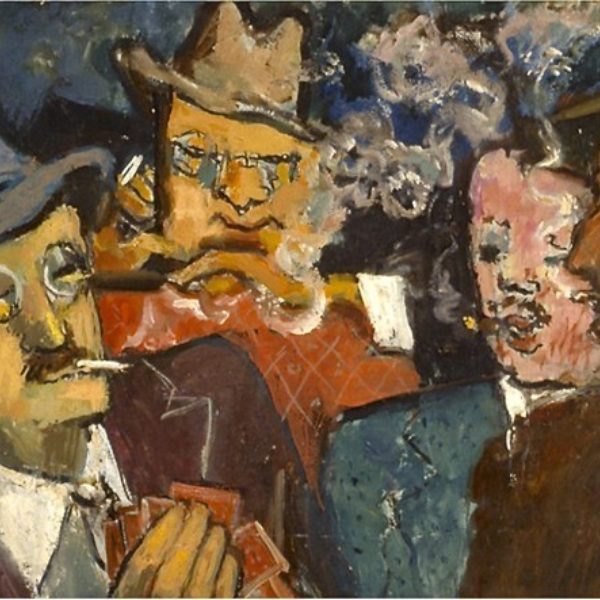

Commuters (1945) signals a shift in Himmelfarb’s art away from his dark-toned urban realism of the 1920s and toward an increasingly abstract aesthetic. Although it, too, represents a scene from daily life—four men passing time with a game of cards during their daily commute—the painting’s formal elements assume greater prominence. Its close cropping, flattened space, bold outlines, and unmodulated areas of color result in an interesting play of forms in the geometric shapes of the figure’s heads, fedoras, and broad shoulders, and the organic plumes of cigarette smoke. In an artist’s statement for a solo exhibition in Milwaukee in 1969, Himmelfarb articulated this process in which he “develop[ed] intriguing ‘thing’ patterns formed by overlapping ornamentation of people shapes, thing shapes, and color shapes. . . . [to] form an active, vibrating, coherent narrative.”

Following his retirement in the late 1960s from Three Dimensions, Himmelfarb dedicated himself full-time to painting and remained an active member of the Chicago arts community until his death in 1976. He was a member of Artists Equity and the Arts Club of Chicago, and lectured frequently to business and professional organizations on the relationship between the fine arts and industrial design. Himmelfarb realized his goal of creating “intriguing ‘thing’ patterns” in his mature works, in which abstracted figures, flattened spaces, and a nearly mechanical technique result in highly decorative patterned surfaces.

Himmelfarb’s artistic career was intimately linked with those of his wife and his son, John Himmelfarb, a successful contemporary artist. In the late 1930s, Samuel and Eleanor designed a modernist house and studio in rural Winfield, Illinois. Its isolated, wooded setting served as an inspiration for Eleanor’s landscapes and profoundly shaped John’s development as an artist. Several exhibitions in the early 1990s showed the works of all three Himmelfarbs together. While sensitive to the artists’ unique sensibilities and vocabularies, critics and curators also noted “shared aesthetic concerns” and “common visual elements” among the three painters, including a commitment to “narrative[s] of nature,” reinvention of dimensional space, and stylized, patterned imagery.

Patricia Smith Scanlan

References

“Art: The Work of Samuel Himmelfarb.” Inland Architect 1, no. 7 (1958). Chicago Artists’ Archives: Himmelfarb Family File. Harold Washington Library Center, Chicago.

“Biographical Notes.” Samuel Himmelfarb: People Paintings and Drawings. Milwaukee: Charles Allis Art Library, 1969.

Falk, Peter Hastings, ed. The Annual Exhibition Record of the Art Institute of Chicago, 1888–1950. Madison, CT: Soundview Press, 1990.

Falk, Peter Hastings, ed. Who Was Who in American Art 1564–1975: 400 Years of Artists in America. Vol. 2. Madison, CT: Soundview Press, 1999.

Galpin, Amy, and Susan Weininger. “Samuel Himmelfarb.” In Elizabeth Kennedy, ed., Chicago Modern, 1893–1945: Pursuit of the New, 121. Chicago: Terra Foundation for the Arts, 2004.

Three Painters: Samuel Himmelfarb, Eleanor Himmelfarb, John Himmelfarb. Quincy, IL: Quincy Art Center, 1994.

Two Generations Chicago: The Influence of Family. Evanston, IL: Evanston Art Center, 1990.

Weinberg, H. Barbara, Doreen Bolger, and David Park Curry. American Impressionism and Realism: The Painting of Modern Life, 1885–1915. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, distributed by H. N. Abrams, 1994.