Romolo Roberti

b. 1896, Montelanico, Italy - d. 1988, Gautier, MS

Romolo Roberti knew at a young age that he wanted to be an artist, and with that in mind stayed in the United States at the conclusion of a 1911 business trip on which he had accompanied his father. The 15-year-old Roberti knew little English, had no money or family, but managed to make his way. Through friends, he got a job as a maintenance man and landscaper at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, where he had the good fortune to meet Professor Christian Midjo, who allowed him to attend a life drawing class for architecture students (there was no art program at Cornell at this time). Midjo became the mentor Roberti sought, and he remained in Ithaca for nine years, working in maintenance, saving his money, and studying with Midjo. He arrived in Chicago in 1922, and enrolled in night classes at the School of the Art Institute (SAIC), painting during the day, and exhausting his savings within eight months. He dropped out of SAIC, never earning a degree, and began supporting himself by working as a painter and decorator, doing faux finishes and decorative stenciling, something he continued to do for the rest of his life, periodically accumulating enough money to allow him to paint without interruption.

In 1927, he moved into the Tree Studios, a U-shaped building in which the commercial spaces on the ground floor subsidized artists’ studios above. The design of the building, with its central courtyard and skylit rooms, maximized natural light in the interior spaces. Tenants of the building ranged from traditionalists such as Pauline Palmer and Karl Buehr to modernists such as John Storrs and Macena Barton. In addition to his teachers at SAIC, Roberti seems to have sought out fellow Tree Studio resident, Wellington J. Reynolds, to replace Midjo as a mentor during this time. It was during this period that Roberti began to exhibit regularly in galleries, with artists’ groups and at the Art Institute juried annuals.

The Tree Studios supplied Roberti with some of the subject matter for his urban scenes, including North State Street (1929), done from a window in the Tree Studio Building overlooking the intersection of State and Ohio. Like many of his images of the built environment from this period, Roberti has constructed his scene in a clear geometric, cubist-inspired Precisionist style so popular in 1920s America. His painting, with its dazzling colors and clear structure, contrasts with Ruth Van Sickle Ford’s image of the same scene done a few years later. Ford, also a resident of the Tree Studios, used a loose painterly style and emphasized the bustling activity of the busy corner. Roberti’s misanthropy made him a poor fit for the active social life of the artists in the building and may have inspired his Peeping Tessies (1930), an image of the skylit roof seen against a backdrop of the Chicago skyline, with its characteristic water towers atop the high rise buildings. The style of the work shares some of the geometric simplification of the Precisionists; the subject displays Roberti’s own penchant for storytelling and humor in the group of nosy women peeking into the artists’ studios below to see the nude models or whatever else was going on.

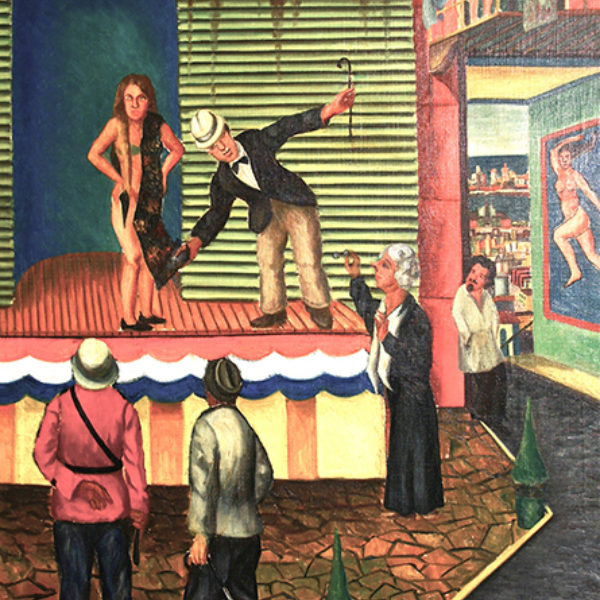

Many artists in Chicago in 1933 and 1934 were inspired by the Century of Progress Fair, and Roberti’s brilliantly colored Untitled (Progress, 1934) focuses on the entertainment area, the Midway, rather than the part of the fair devoted to the technological and scientific advances of the machine age. A carnival barker on the stage is about to unveil a stripper in front of a few onlookers including an older woman who stands as close as she can get to observe the event through her monocle and a man wearing an artist’s smock (and resembles Roberti) who stands off to the side, observing the scene. Roberti’s humor is evident, as is his role as the outside observer.

While many of his paintings of this period show an engagement with modernist styles, at the same time he also did a series of large paintings based on Dante’s Inferno that are eccentric and strange, often surreal. In the 1930s, like many other American artists, he produced many streetscapes and rural scenes that conform to the dominant American Scene painting of the time. He worked briefly on the first of the government supported art projects, the Public Works of Art Project, in 1934.

After his seven-year marriage ended in 1940, he began to travel, taking on jobs ranging from house cleaner and repairman to commercial projects such as overseeing the redecoration of the commons at the University of Northern Iowa, in Cedar Falls. He exhibited his work in Des Moines, Cedar Falls, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, and New Orleans during this period. He settled in Gautier, Mississippi, near his only son and his family in 1967, continuing to travel and paint until shortly before his death in 1988.

Susan Weininger

Reference

Susan S. Weininger, “‘My Duty Is to Paint’: The Art of Romolo Roberti.” In Romolo Roberti: An American Original. Chicago: Robert Henry Adams Fine Art, 2007.