Morris Topchevsky

b. 1899, Bialystok, Poland - d. 1947, Chicago, IL

Morris Topchevsky was born in the cosmopolitan, and majority Jewish, city of Bialystok, Poland, which, in the early twentieth century, was part of the Russian Empire. The Topchevsky family was victimized in the 1906 Bialystock pogrom, but did not leave the city for the United States until 1911. Topchevsky’s experience of ethnic violence—which he would witness again during the 1919 race riots in Chicago—was the basis of a lifelong commitment to racial equality and the ideals of Marxist social thought. A member of the Communist Party USA, he was renowned as Chicago’s most outspokenly radical artist.

Topchevsky’s work as an apprentice to a sign painter led him to take art classes at Hull House and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). After teaching art at Hull House for a brief time, Topchevsky traveled to Mexico in 1924, where he studied and worked for several years. He developed a passion for the people and landscapes of Mexico and formed lasting friendships with the muralists Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco. When he returned to Chicago in the early 1930s, Topchevsky began a long association with the Abraham Lincoln Centre, a Unitarian social settlement founded in 1905 by the reverend Jenkin Lloyd-Jones, uncle of architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Located at 39th Street and Cottage Grove Avenue—bordering the black belt whose swelling population was constrained by restrictive covenants—the Centre served the local African American population and promoted an aggressively socialist political line.

Topchevsky was a leading member of the Chicago branch of the John Reed Club, a nationwide association of writers, artists, and intellectuals who were interested in the goals of the Russian Revolution and in promoting a culture revolving around issues of labor. The Chicago Club, whose members included writers Richard Wright and Nelson Algren, and artists Mitchell Siporin and Edward Millman, was especially influential. Topchevsky was also a leader of the Chicago Artists Union, and took part in a sit down demonstration in 1937 (with Mitchell Siporin and Adrian Troy) to protest the policies of the Illinois Art Project’s Director at the time, Increase Robinson.

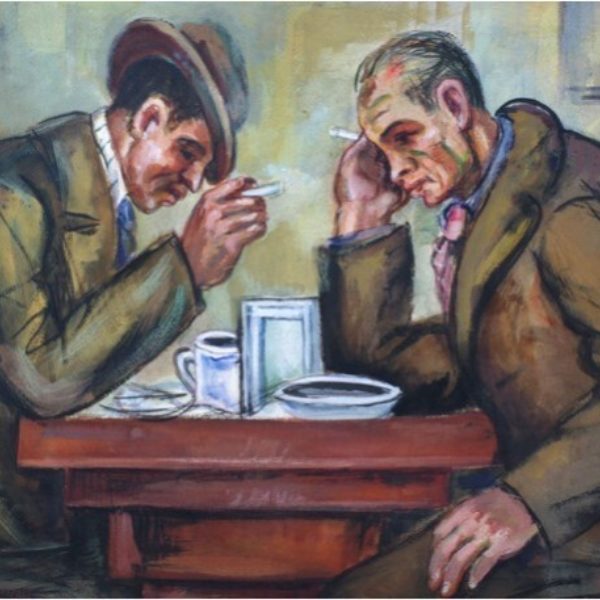

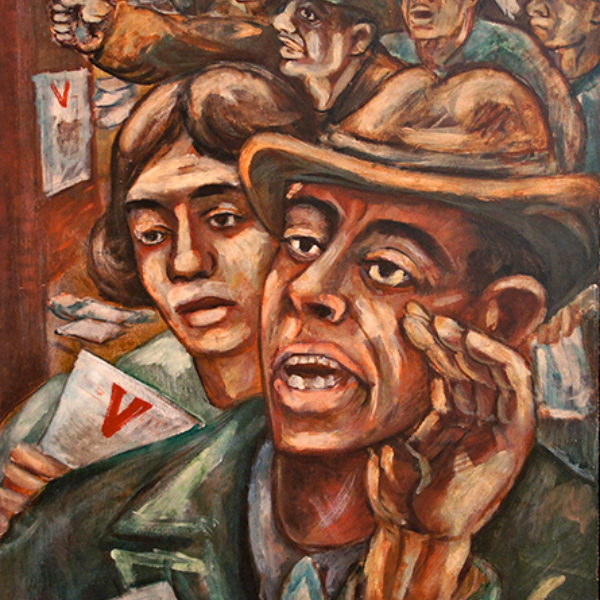

Works such as Leaflets (Double V) and Strike Against Wage Cuts show Topchevsky’s concern for themes of labor and class struggle. Topchevsky also retained a strong interest in the fate of Jews in both Europe and America, and in 1937, he took part in a project to raise funds for a Jewish autonomous region in Siberia, devised by Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, called Birobidjan. Topchevsky’s contribution to the Birobidjan Folio, To a New Life, features a family led by a man who holds a hammer and a blueprint for a planned future—a common trope of revolutionary art of the 1930s. Topchevsky’s most important contribution, however, may have been as a teacher, especially to young black artists who grew up nearby. Both Charles White and Margaret Burroughs took classes with him, learning not only about art but also social thought and activism.

A deeply admiring profile of Topchevsky by Chicago Daily News art critic C. J. Bulliet captures the artist’s identification with issues facing African American artists:

There is an enormous amount of talent on the south side, he says, particularly among the Negroes, who have a kinship with the Mexicans in “having a greater hold on life” than the average American. The Negro, he believes, is gradually finding himself, no longer aping white people, but examining and following racial impulses.

The greatest obstacle in the way, says Topchevsky, who sometimes takes picturesque liberties with Noah Webster’s language, are “mysticism and prejudice.” By “prejudice” he means the well known race prejudice of white versus black, but by “mysticism” he doesn’t mean anything in the Negro psychology akin to “voodooism." The “mysticism” is the “mysticism” read into the cultured Negro by his white brethren. If the Negro does something worthwhile, he is regarded as a phenomenon, something “mystical,” beyond average understanding. Whereas, to Topchevsky the Negro of talent is just another talented human being.

Daniel Schulman

References

Bulliet, C. J. “Artists of Chicago, Past and Present, no. 70: Morris Topchevsky.” Chicago Daily News, June 27, 1936.

Jacobson, J. Z. Art of Today, Chicago, 1933. Chicago: L. M. Stein, 1933.

Topchevsky, Morris, papers. Pamphlet file, P-21473. Ryerson Library. Art Institute of Chicago.