Gregory Orloff

b. 1890, Kief, Ukraine - d. 1981, Union Pier, MI

Gregory Orloff was born in 1890 in Kiev and began his early art training with painter Vyacheslav Korenev at the Kiev Academy of Art. He continued his studies in the United States, first at the National Academy of Design in New York with Charles Curran and Ivan Olinsky, and subsequently with Karl Buehr at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he absorbed his teachers’ preferences for figurative subjects, leisure themes, and the coloristic and decorative effects of Impressionism. Recalling his academic training, Orloff later stated that he had “to unlearn and undo what I had acquired.”

Orloff made his mark in Chicago in the mid-1920s, exhibiting portraits and scenes of daily life with the Chicago Society of Artists, of which he was a member; the progressive Chicago No-Jury Society of Artists; and at the venerable annuals of the Art Institute of Chicago (1925–35); and other venues. Orloff’s early reputation rested largely upon his work in portraiture, which critics praised for showing a keen perception of subjects. He soon found the genre stultifying, however, and set his sights on more complex compositions in a variety of media.

Many of Orloff’s paintings from the 1930s feature subjects drawn from daily urban life, leisure, and entertainment with an optimism and accessible narrative style characteristic of American scene painting. Spring Song (1930 or 36) evokes a reassuring vision of urban life and racial relations in Chicago at this time. Set against the backdrop of a row house, three young children chant a familiar tune on a front stoop, a key locale for social encounters in the city. Orloff’s interests in the human figure and composition are apparent in the interplay between the weighty, rounded forms of the children and the rigid horizontal and vertical architectural elements. A chromatic progression from the warm, earthy tones of the wagon and the boy’s clothing to the brilliant white dresses of the girl and doll at the top creates a further sense of spatial recession and movement on the canvas.

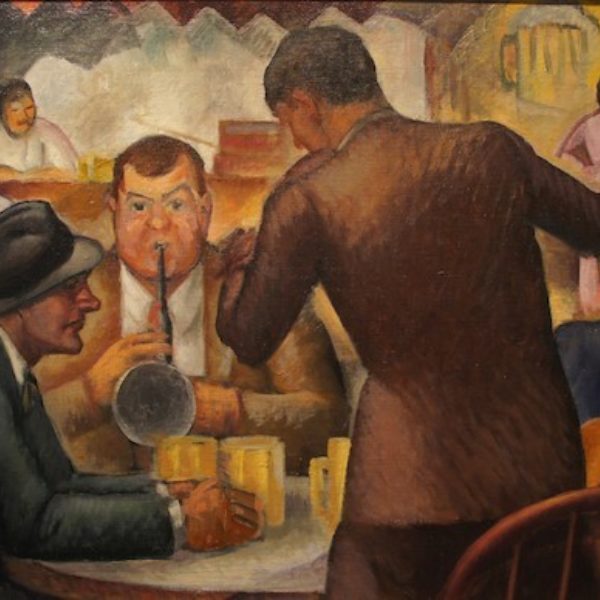

Orloff similarly depicted a festive musical scene in Musicians at Century of Progress (1934), which highlights one of the fair’s numerous entertainment venues—a vast, raucous beer hall. Crowded around a small table in the foreground, a ruddy-cheeked saxophone player and a raven-haired cellist blare a lively strain for the bar’s patrons. Small clusters of revelers in the background enliven the atmosphere and enhance the picture’s narrative. The interplay of stylized figures, boldly outlined curvilinear and geometric shapes, dramatic lighting, and rich colors results in an animated composition that engages the senses. The painting echoes the tenor of optimism surrounding the Century of Progress and the promise of better days after the Depression.

In contrast, Orloff mutes the cacophony of urban noises in a scene of contemplative reverie in Solitude (1933). A lone woman enjoys the tranquility of a lakefront park, its cool water and lush gardens a welcome respite from the densely built surrounding metropolis. The elegant outline of the female figure, the twisting column of the tree trunk, and the profusion of foliage are grounded by the geometry of the vertical posts and horizontal slats of the bench and the circular rim of sand at the water’s edge. A cool palette of greens, blues, and pale earth tones prevails, applied with a subtle dexterity to achieve a pastel-like effect. A nearly identical scene appears in a woodcut of the same title by the artist, also dated 1933. Although the image is reversed in the print version, the figure, bench, trees, and beach maintain their positions within the composition against a more expansive background.

In an interview in the mid-1920s, Orloff maintained that his efforts in printmaking bore a strong connection to his color work. He characterized his woodblock prints as “direct, strong, and brutal,” and credited them as a “decided influence” in his approach to painting, one that began to privilege composition over subject matter and color. Like many contemporary artists, Orloff generated hundreds of woodcuts, etchings, and lithographs under the auspices of the Federal Art Project during the Depression. While his renderings often echo the uplifting subjects of his paintings, they also address the darker side of American life in their gritty depictions of steel mills, factories, laborers, and urban sprawl. Throughout the 1930s, Orloff showed his work at Midwest and East Coast venues and, under the auspices of the Federal Art Project, he executed several mural projects in Chicago area schools, including Lake View High School.

Orloff continued to create and exhibit paintings and prints in the 1940s and 1950s, while diversifying his production to encompass illustrations for works of fiction and school textbooks. During these decades, he taught art classes and remained active in the cultural community in and around Union Pier, Michigan, where he had relocated earlier in his career. The recently rediscovered corpus of Orloff’s paintings, prints, and drawings has sparked renewed interest among collectors and scholars in the artist’s lengthy, successful career and prolific output.

Patricia Smith Scanlan

References

Falk, Peter Hastings, ed. The Annual Exhibition Record of the Art Institute of Chicago, 1888–1950. Madison, CT: Soundview Press, 1990.

———, ed. Who Was Who in American Art 1564–1975: 400 Years of Artists in America. Vol. 2. Madison, CT: Soundview Press, 1999.

“The Front Cover.” Chicago Daily Tribune. April 13, 1947.

Gregory Orloff Art & Artist File, Smithsonian American Art Museum/National Portrait Library, Washington, DC, May 16, 2013.

Harpaz, Nathan. Gregory Orloff: Prints from the Great Depression. Des Plaines, IL: Oakton Community College, 2009.

Jacobson, J. Z., ed. Art of Today: Chicago 1933. Chicago: L. M. Stein, 1932.

Jewett, Eleanor. “Works of Chicago Artists on Display in State Exhibition.” Chicago Daily Tribune. November 2, 1927.

———. “News of Exhibitions.” Chicago Daily Tribune. November 17, 1929.

———. “South Side Art Group Opens Show of Brilliant Pictures.” Chicago Daily Tribune. January 9, 1930.

———. “Orloff Sticks to Pattern in His Paintings.” Chicago Daily Tribune. April 13, 1933.

———. “Army Artists’ Show Proves Drawing Card.” Chicago Daily Tribune. August 29, 1943.

Mavigliano, George J., and Richard A. Lawson. The Federal Art Project in Illinois. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1990.

“No-Jury Artists Open Exhibit This Morning.” Chicago Daily Tribune. January 10, 1927.

Schulman, Daniel. “‘White City’ and ‘Black Metropolis’: African American Painters in Chicago, 1893–1945.” In Chicago Modern, 1893–1945: Pursuit of the New, edited by Elizabeth Kennedy, 39-51. Chicago: Terra Foundation for American Art, 2004.

“Set Art Exhibit at Three Oaks.” Herald-Press [St. Joseph, MI]. June 8, 1955.

Sparks, Ethel. “A Biographical Dictionary of Painters and Sculptors in Illinois 1808–1945.” PhD diss., Northwestern University, 1971.

Weininger, Susan S. “Modernism and Chicago Art: 1910–1940.” In The Old Guard and the Avant-Garde: Modernism in Chicago, 1910–1940, edited by Sue Ann Prince, 59–75. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

———. “Gregory Orloff.” In Chicago Modern, 1893–1945: Pursuit of the New, edited by Elizabeth Kennedy, 138. Chicago: Terra Foundation for the Arts, 2004.

———. “‘The Spirit of Change’: Modernism in Chicago.” In Chicago Painting 1895 to 1945: The Bridges Collection. Urbana: University of Illinois Press with the Illinois State Museum, 2004, 56–81.

WTTW. “Gregory Orloff , Terra Foundation Artbeat Special.” WTTW Chicago Tonight Web site. Video file. http://chicagotonight.wttw.com/2010/09/28/gregory-orloff-terra-foundation-artbeat-special (accessed May 6, 2013).

Yochim, Louise Dunn. Role and Impact: The Chicago Society of Artists. Chicago: Chicago Society of Artists, 1979.