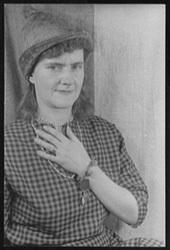

Gertrude Abercrombie

b. 1909, Austin, TX - d. 1977, Chicago, IL

Gertrude Abercrombie was the only child of Tom and Lula (Janes) Abercrombie, who were performing with a traveling opera company in Texas when she was born. Their work necessitated an itinerant lifestyle and Gertrude lived in a number of places, including Berlin, where she became fluent in German as a child. The outbreak of World War I in 1914 forced the family to move back to the United States. Both of Abercrombie’s parents were firmly rooted in the Midwest and they settled first in the western Illinois town of Aledo, where Tom’s family lived, before moving, in 1916, to the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago, where Abercrombie spent the rest of her life.

Abercrombie’s childhood experiences left her with a love of languages (her degree from University of Illinois in 1925 was in Romance Languages) and wordplay (she loved puns, anagrams, crossword puzzles, and games of all sorts), music (she was an accomplished musician who had perfect pitch, although she favored jazz over the classical music that dominated her childhood), and a deep connection with middle America. She looked forward to the summers she spent in Aledo with her Abercrombie cousins (the closest thing she had to siblings), and used the landscape and landmarks of the area around the town as subjects for her art throughout her career.

Although she took many art classes in college and studied part-time after graduation at the American Academy of Art and the School of the Art Institute, Abercrombie’s appointment to the Public Works of Art Project (the first of the government supported arts programs) in 1933 made her feel like a professional artist for the first time, and allowed her to move to her own apartment in the Weinstein Building in Hyde Park, which was occupied by many artists and writers who became lifelong friends. She was also introduced to the jazz musicians who became such a large part of her life through her close friends, the artists Charles Sebree and Karl Priebe.

At this time she began to exhibit at the Art Institute Annuals and galleries in both Chicago and New York, and to develop the characteristic personal style that defines her work. From the beginning, her work and life were intertwined. After she married lawyer Robert Livingston in 1940 and moved to the house on Dorchester Avenue, where she remained until her death in 1977, her life was filled with Saturday night parties and Sunday afternoon jam sessions. She thought of herself as the “other Gertrude” who hosted a Chicago Salon including jazz musicians, writers, and artists; the liquor flowed freely and she presided imperiously as the self-appointed “Queen of Chicago.”

Her work always included objects of personal significance and often a self-portrait (as in The Ivory Tower, where she is shown painting a scene from the room in the top of the tower, also creating a picture within a picture, another frequently used device). In this painting, the tower itself looks like a large chess piece, again referring to her own interest in the game. The landscape resembles the area around Aledo. Along with the Whale and Lighthouse and Untitled (Ballet for Owl), The Ivory Tower is representative of the most productive and accomplished period of Abercrombie’s life. The oft-repeated moon, cats, barren tree, owls, Victorian furniture, white stoneware, and carnations, all take on the power of personal emblems in her work and testify to her presence even in the absence of a figure. In addition, her work has a carefully controlled palette and an airless, austere quality that contrasts with the more chaotic conditions of her life.

Abercrombie used painting to manage her world and the psychic pain that she admittedly suffered. She transformed her internal conflicts into works of great power, mystery, and resonance. Although she suffered from a series of alcohol-related illnesses during the last decade of her life and became an invalid confined to one part of her home, she continued to work, leaving us her private and eccentric but enormously appealing and significant work.

Susan Weininger

References

Abercrombie, Gertrude. Papers, Smithsonian Institution, Archives of American Art.

Weininger, Susan. “Fantasy in Chicago Painting: ‘Real “Crazy,” Real Personal, and Real Real,’” and “Gertrude Abercombie.” In Elizabeth Kennedy, ed. Chicago Modern, 1893–1945: The Pursuit of the New, 67–78 and 80,162. Chicago: Terra Foundation for the Arts, 2004.

Weininger, Susan. “Gertrude Abercrombie.” In Rima Lunin Schultz and Adele Hast, eds. Women Building Chicago: 1790–1990. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2001, 12–14.

Weininger, Susan, and Kent Smith. Gertrude Abercrombie. Springfield: Illinois State Museum, 1991.

Artist image: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection, LOT 12735, no. 4 [P&P], Item #2004662470