David Bekker

b. 1897, Vilna, Poland (now Lithuania) - d. 1956, Chicago, IL

David Bekker was born in Vilna, Poland (now Lithuania), on May 1, 1897. He began night classes at age 11 at the Art School in Vilna, studying with sculptor Mark Antokolsky. At age 14, he emigrated to Palestine, increasingly aware of a “Jewish strain” in art. There, he studied with Abel Pann, a painter, and Boris Schatz, a Vilna sculptor and founder of the Bezalel Art School. Pann left Palestine several years later, and Bekker left for Paris to continue his studies. During World War I, while stranded in Sofia, Bulgaria, Bekker did some carvings in wood and metal that attracted the attention of the official engraver for the Count of Rumania, who gave him a job in Bucharest. He stayed for a year, designing coins and medals, carving portraits in ivory, and engraving plates for official papers. Subsequently, Bekker lived in London and the United States, landing in Boston, before eventually going to Denver. He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Denver for a year.

Bekker likely came to Chicago in the late 1920s or early 1930s as a show of linocuts was mounted by the Jewish Women's Art Club of Chicago in 1932, and he produced murals in Illinois public buildings for the Works Progress Administration (WPA) during the Depression. The contemporary critic, C. J. Bulliet declared that his work for the WPA had “engendered an American school” of art. He was also featured in a solo exhibition at the Art Institute's Room of Chicago Art in 1943.

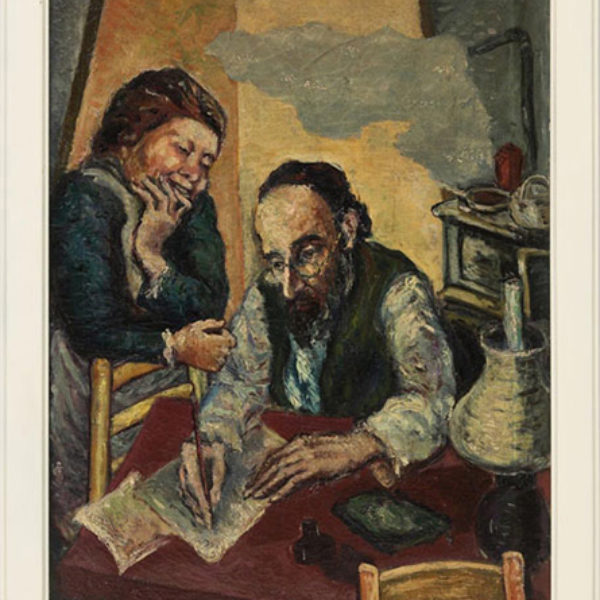

Bekker often depicted scenes of Jewish life from the past in modernist idioms of the present, reflecting his interest in the work of modern artists Matisse, Cezanne, and Van Gogh. He described his artistic outlook: “As a descendent of the persecuted Jewish people. . . I feel impelled to give form as my work to pathos, sorrow, strife and triumphant joy.” He captured the contrast between the old country and the new in two paintings, Letter to the New Country and Letter from the Old Country, both made in 1936. In the former painting, Bekker depicts the old world using modernist forms: a cubist interior of angled walls, with a tilted table top and chairs askew, perhaps to reference the political upheaval and instability of Europe—especially for Jews—at that time. The traditional couple bear the hallmarks of the old world context: the woman stands behind a chair, wearing an apron as if ready to serve her husband hot tea, the boiling water steams in the background. The man sits at the kitchen table, wearing a vest and white shirt, his elongated fingers carefully putting pen to paper. In contrast, Bekker depicts the young couple receiving this Letter from the Old Country as more prosperous, with brighter clothing and posed with more intimacy, leaning in to each other as they read news from their family back home. While the elder couple is situated in a small, cramped kitchen where we can almost smell the aromas and imagine the generations who have lived here before, the young couple stand against a blank background—as if to reflect the blank slate that the new country represents. A woodcut included in the 1937 Birobidjan portfolio, Bronx Express, also illustrates this contrast between tradition and modernity, portraying a Yiddish-speaking man riding the crowded subway train.

Lisa Meyerowitz

References

Bekker, David. Pamphlet file P-02449. Ryerson Library. Art Institute of Chicago.

Bulliet, C. J. “Artists of Chicago, Past and Present: No. 69 David Bekker.” Chicago Daily News, June 20, 1936.

Jacobsen, J. Z. The Art of Today: Chicago, 1933. Chicago: L. M. Stein, 1932. pp. 139–40;

Myths and Moods: Linocuts by David Bekker. Chicago: Jewish Women’s Art Club, 1932.

Oakton Community College. A Gift to Biro-Bidjan: Chicago, 1937: From Despair to New Hope. Exhibition website, www.oakton.edu/museum/bekker.html.

Yochim, Louis Dunn. Harvest of Freedom: A Survey of Jewish Artists in America. Chicago: American References, 1989.