Abraham Pollack

b. 1864, Kerch, Ukraine - d. 1933, Chicago, IL

Abraham Pollack was born in 1864 in Kerch, an ancient port city in eastern Crimea, where he spent his youth. At fourteen, he immigrated to the United States with the help of his older brother, Jacob, who had preceded him there and paid for Abraham’s passage. Pollack settled in Chicago, where he attended school and worked at odd jobs for several years before opening a photographic studio in his early twenties. Soon after his marriage to a widow with a teenage son, however, he abandoned the studio and began working as a tailor’s salesman to support his new family.

Around 1923, after nearly twenty-five years as a clothing peddler, he “tore himself away from worldly obligations and began to paint.” One account relates that a friend insisted on showing some of Pollack’s sketches to artist Rudolph Weisenborn, who exclaimed, “This man is a genius, a primitive artist!” Both Pollack’s life and his art fueled this lionization as “the great American primitive,” a freethinking, self-taught artist who worked outside the academic tradition. Chicago critic C. J. Bulliet touted Pollack’s renunciation of a conventional career, his unique vision, and his crude and expressionistic technique as signs of an authentic genius. Pollack’s paintings received notice among “enlightened” circles when they were first shown in a 1927 exhibition of the Neo-Arlimusc, an independent group founded by Weisenborn that was dedicated to bringing together artists, writers, musicians, and scientists. A critic and a psychiatrist lectured on Pollack’s primitive style and his primitive unconscious, thus affirming the artist’s outsider status. The following year, his painting The Marriage Broker was shown in the Art Institute of Chicago’s Annual Exhibition of American Paintings and Sculpture.

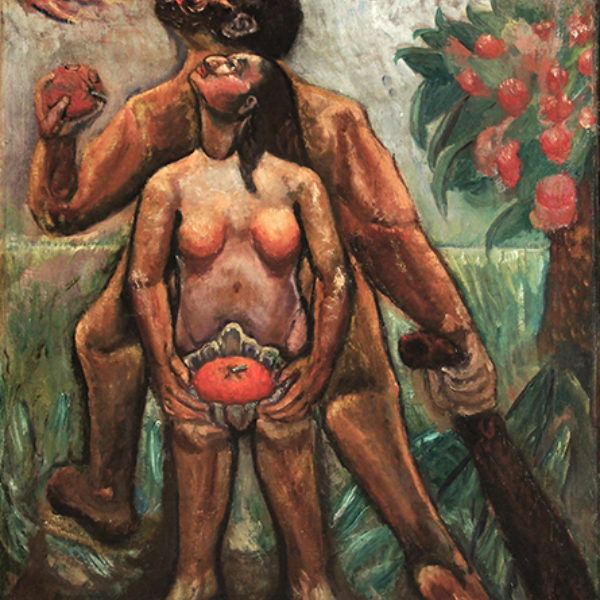

Pollack’s subjects from this period appear to have been drawn largely from contemporary Jewish life and religion. He reportedly sought material in “Jewish sweatshops” and “Chicago’s ghetto” for pictures such as A Corner of Maxwell Street (1927), a bustling streetscape of the predominantly Jewish Chicago neighborhood. The painting was exhibited in the 1927 Neo-Arlimusc exhibition and reproduced in Bulliet’s lengthy 1939 article about the artist. Titles of other works—Crucifixion, Capture of Samson (1928) and Revolt in Paradise (1932)—reference dramatic biblical passages that lent themselves to Pollack’s vigorous technique and passionate expression. Capture of Samson is an apt display of Pollack’s primitive, unbridled creativity. At the center, the massive figure of Samson strains against a thick rope around his neck while a sea of writhing, muscular, nude Philistines pins his limbs and others prod him and poke at his eyes. Their grotesque faces, crudely painted bodies, and raw, earthy skin tones accentuate the bestial nature of their attack. The recumbent figure of Delilah in the lower left corner provides a stable anchor to this swirling chaos. Her flowing hair, scantily clad form, and jeweled adornments allude to her role as seductive temptress, while the pair of shears in her right hand attests to her destructive power over the mighty hero. Forcefully painted with thick black outlines around the figures and bold slashes of pigments, the canvas embodies Bulliet’s description of the artist: “Pollock’s [sic] soul was a volcano. It was lava he poured onto his canvases.”

Like a volcano, Pollack’s brief, meteoric rise quickly came to an end. He struggled financially in Chicago, became a tramp, and hitchhiked to New York with a load of pictures. Following a disastrous stay there, which left Pollack penniless and homeless, he returned to Chicago, where he continued to paint but failed to sell his work. Artist A. Raymond Katz befriended Pollack during this difficult time and tried, unsuccessfully, to salvage his career with a show at the Little Gallery in the tower of the Auditorium Building in late 1932. As Pollack’s health declined, he moved into a home for the elderly and, eventually, into a mental institution before his death in 1933.

Patricia Smith Scanlan

References

Bulliet, Clarence J. Apples and Madonnas: Emotional Expression in Modern Art. Chicago: Pascal Covici, 1927.

———. “Artists of Chicago Past and Present, No. 92: A. L. Pollock [sic].” Chicago Daily News. June 24, 1939.

———. Undated clipping. Rudolph Weisenborn Pamphlet File P-05500. Ryerson Library, Art Institute of Chicago.

Falk, Peter Hastings, ed. The Annual Exhibition Record of the Art Institute of Chicago, 1888-1950. Madison, CT: Soundview Press, 1990.

Fourteenth Census of the United States: 1920—Population. Chicago, Cook County, Illinois. Enumeration district 1959. Heritage Quest Online.

Jewett, Eleanor. “Catalogue of A Century of Progress Art Exhibit at Institute Wins Hearty Praise of Visitors.” Chicago Daily Tribune. July 9, 1933.

Weininger, Susan. “‘The Spirit of Change’: Modernism in Chicago.” In Chicago Painting 1895 to 1945: The Bridges Collection. Urbana: University of Illinois Press with the Illinois State Museum, 2004.

Zorbaugh, Harvey Warren. The Gold Coast and the Slum: A Sociological Study of Chicago’s Near North Side. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1929.